Mangan Farm is the ancestral homestead of Thomas Kavanagh and Margaret ‘Judith’ Cleary, located between Enniscorthy and the Blackstairs mountains – about 5 miles from each. Our Nolan family traces back to the Kavanagh’s through our maternal line – Mary Anne Roche, daughter of Marcella Nolan, daughter of Ann Mernagh, daughter of Anne Kavanagh, daughter of Thomas and Margaret Kavanagh.

Thomas Kavanagh was born in 1774, and as the eldest son of Dennis Kavanagh, inherited the family leasehold farm in 1799 when Dennis died. In terms of Irish leaseholds at the turn of the century, it was quite a large property, totalling around 168 acres – unusual for the time, when most families had little more than an acre or two to farm.

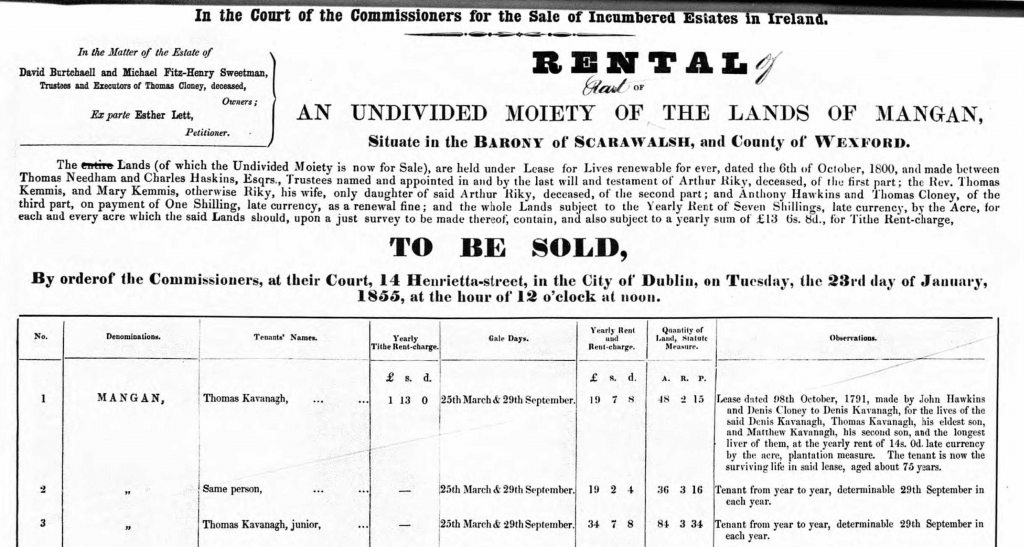

Mangan (An Mongán) is in the parish of Templeshanbo, barony of Scarawalsh, and church records for the nearby Kiltealy and Templeshanbo churches are not available for the early 1800’s, but we can learn more from the land and property records. The Landed Estates Court Rentals 1850-1885 records are often quite specific and tell of the family relationships. In the case of the Kavanagh’s, the outline of the family of Thomas Kavanagh is recorded in 1855, when part of the land was put up for sale by the owners. The original lease dates back to 28th of October, 1791, when Denis Kavanagh leased the land from John Hawkins and Denis Cloney.

The details of the lease are as follows: Mangan. Tenant Thomas Kavanagh. Lease dated 28th October 1791, made by John Hawkins and Denis Cloney to Denis Kavanagh, for the lives of the said Denis Kavanagh, Thomas Kavanagh, his eldest son, and Matthew Kavanagh, his second son, and the longest liver of them, at the yearly rent of 14s. 0d. late currency by the acre, plantation measure. The tenant is now the surviving life in said lease, aged about 75 years. 48 acres of land. Further: Thomas Kavanagh, 36 ares. Thomas Kavanagh jr., 84 acres.

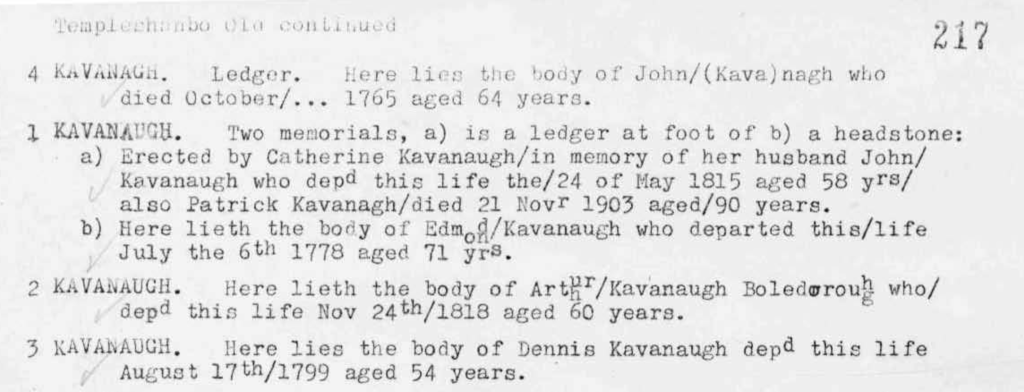

Dennis Kavanagh, Thomas’s father, died in August 1799. Brian Cantwell [>] suggests that he may have been involved in the 1798 rebellion, though no direct evidence exists. Dennis is buried in Templeshanbo Old graveyard.

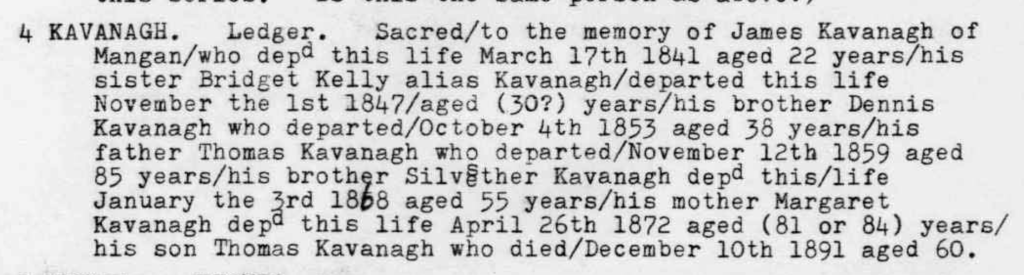

The above is taken from Brian Cantwell’s “Memorials of the dead”, a record of gravestones in Wexford churchyards. In another volume, for Kiltealy, we find our ancestors listed – these are the children of Thomas Kavanagh and Margaret Cleary.

From the above, then: Children of Thomas Kavanagh (died 12-Nov-1859) & Margaret Cleary (died 26-Apr-1872):

- Silvesther Kavanagh died 03-Jan-1868 aged 55 [born c. 1813]

- Dennis Kavanagh died 04-Oct-1853 aged 38 [born c. 1815]

- Bridget Kavanagh (later Kelly) died 01-Nov-1847 aged 30 (?) [born c. 1817]

- James Kavanagh of Mangan, died 17-Mar-1841 aged 22 [born c. 1819]

In the St. Mullins graveyard, the following is listed by Col. Vigors c. 1890 [>]:

"James KAVANAGH of Ballybeg, died 1779. Mary CLONEY als.

KAVANAGH, sister to James, of Monohore, Co. Wexford and

wife of Mr. Denis CLONEY, who depd this life Oct. 20,

1782 aged 30. Gerald KAVANAGH, son to Felix, died 1789

aged 49; and also Mrs. Katherine KAVANAGH alias FURLONG

wife to the said James. Mary, Terance and Gerald depd

this life Decr 22nd, 1803 aged 80 years Also the body

of her daughter, Mrs. Helen KAVANAGH who departed this

life on the 10th day of December 1838, aged 82 years."

Also are deposited underneath the remains of the undermentioned'

Thomas CLONEY better known for the last 40 years as General

CLONEY, the friend and co-labourer of the Great O"CONNELL

in all his measures for the amelioration of the people of

Ireland who departed this life

Feb. 22, 1850 Aged 76 years"

----------

"This tomb was erected by Thomas CLONEY of Graig,

in the Co. Kilkenny, in remembrance of his parents,

underneath interred, whose ancestors remains he had

carefully collected from the adjoining vault."Mary Cloney alias (als.) Kavanagh indicates the format of the “alias” commonly used in Ireland. Alias = “nee”, or “maiden name”. Mary died October 20, 1782, at the age of 30, and was the wife of Denis Cloney, and lived in Monohore (location not found). Her brother was James Kavanagh of Ballybeg.

Thomas Cloney – her son – is detailed further below.

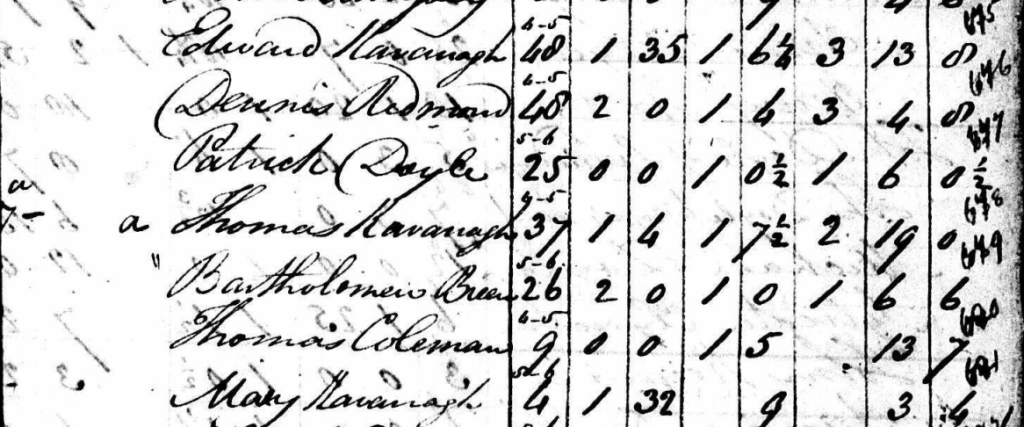

In the 1824 Tithe Aplotment book [>], a list of names for Mangan includes Thomas Kavanagh (37 acres), Edward Kavanagh (48 acres) and Mary Kavanagh (4 acres). The tithes were a deeply unpopular tax on Irish leaseholders, to finance the Protestant Church of Ireland, even though those that were forced to pay were Catholic.

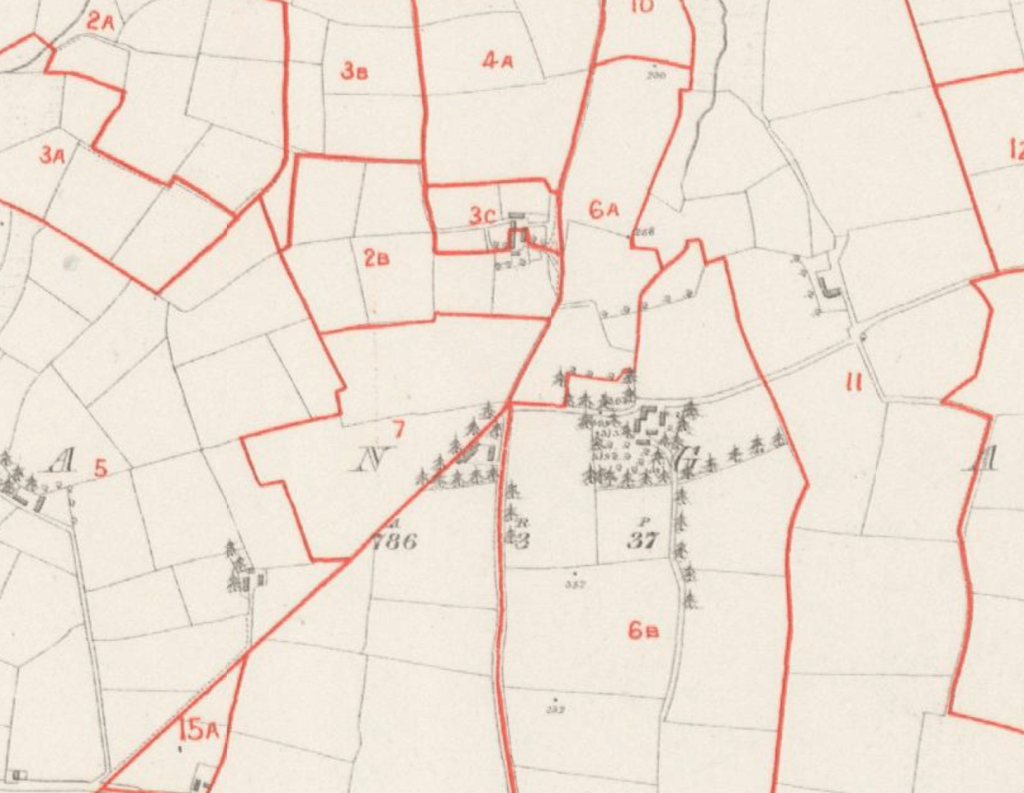

The location of Mangan Farm is shown here in the Griffith’s Valuation record from 1853 [>], numbered 6a, 6b and 7.

The boundaries are the same today (2022) – showing the Blackstairs mountains in the background.

Family of Thomas Kavanagh and Margaret ‘Judith’ Cleary

Anne Kavanagh, our direct ancestor, was born about 1820 at Mangan, and married John Mernagh. Their daughter Annie Mernagh married Martin Nolan, and had a daughter Marcella Nolan.

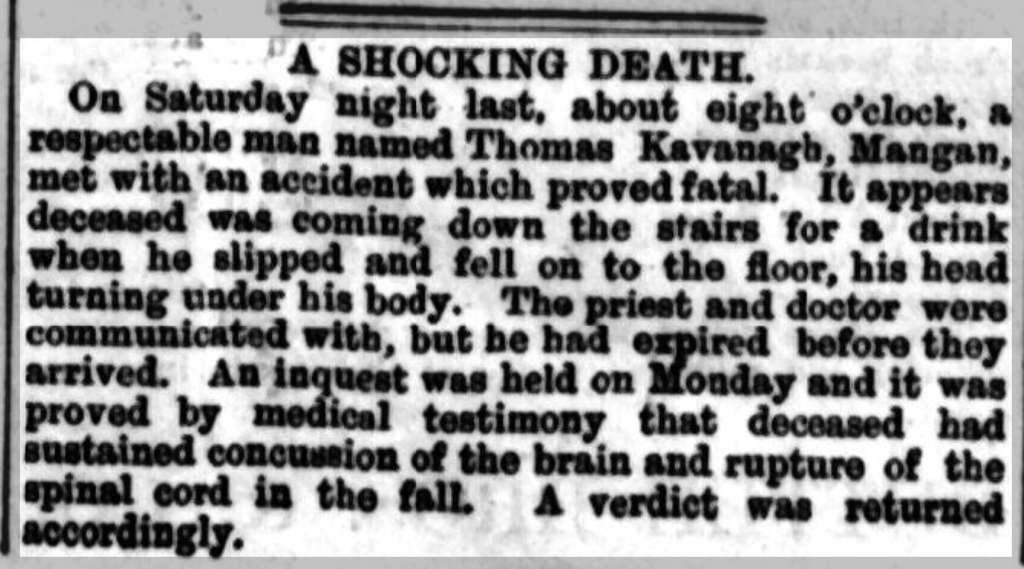

Thomas Kavanagh junior, a brother of Anne Kavanagh, married Catherine Bracken. Their daughter Kate married Thomas Nolan (of Matthew Nolan and Mary Stafford, Killane). He died on December 6th, 1891 in a fall coming down the stairs.

The rest of the family are as follows (from the Gravestone in Kiltealy, Cantwells Memorials):

James Kavanagh of Mangan, who dep’d this life March 17 1841 aged 22

his sister Bridget Kelly alias Kavanagh departed this life Nov 1st 1847 aged (30?) years

his brother Dennis Kavanagh who departed October 4th 1853 aged 38 years

his brother Sylvester Kavanagh depd this life Jan 3rd 1868 aged 55 years

his son Thomas Kavanagh who died December 10th 1891 aged 60.

Anne Kavanagh

Anne Kavanagh, daughter of Thomas Kavanagh and Margaret Cleary, was born around 1820. She married John Mernagh about 1850, and died in 1904.

General Thomas Cloney

Mangan Farm was originally leased by Dennis Kavanagh (Thomas Kavanagh’s father) from Denis Cloney (1732-1798), a properous landowner from Moneyhore (just south of Mangan), who owned about 300 acres in Mangan and nearby areas. Denis Cloney’s mother was also a Kavanagh – Mary Kavanagh – though she was from Ballybeg, Co. Carlow and not likely closely related to Thomas Kavanagh.

Thomas Cloney (1773-1850), Denis’s son, took over the management of his landholdings when Denis died in 1798, and can be seen listed on the Landed Estates Court Rentals record above for Mangan. Thomas was better known as General Thomas Cloney, a rebel leader in 1798. He fought at the Battle of Three Rocks, Battle of New Ross, Battle of Foulksmills (or Goff’s Bridge) and led the attack on Borris House. He was often subsequently referred to as ‘General’ Cloney because of this. New Ross was one of the bloodiest battles in Irish history. This summary of Thomas’s life is from Des Kiely.

GENERAL THOMAS CLONEY – The rebel leader from Moneyhore

Thomas Cloney was born in 1773 in Moneyhore in the parish of Davidstown near Enniscorthy to middle-class Catholic parents. His father Dennis Cloney was a wealthy farmer and middleman who rented about 300 acres of farmland. His mother Mary (née Kavanagh) was a native of Ballybeg, across the border in Co. Carlow but she died when Thomas was only seven. He grew into a six foot two inch young man and helped run the farm for his father who was in poor health.

REBELLION

In the 1790s there were rumblings of discontent throughout County Wexford. Catholics were protesting against the enforced payment of tithes to the Protestant church. With reports of murders and floggings by Orange yeomen, there were feelings of terror in the county. On 26 May 1798 twenty cavalry from Camolin arrived in the Harrow near Boolavogue and burned down the cabin of a suspected rebel. A fight followed with a group of local men armed with pikes. Two of the cavalry were killed. This was the start of the Wexford Rebellion. Fr. Murphy, a curate in Kilcormick near Boolavogue, acted quickly and sent word around the county that the rebellion had begun and organised raids for arms on loyalist strongholds. Membership of the United Irishmen numbered about 280,000 sworn members in the whole country.

ENNISCORTHY

There was rebel success at Oulart Hill, about eight miles outside Enniscorthy, where a crowd of over 4,000 massacred all but five of a party of 110 soldiers. This was followed by a rebel attack on Enniscorthy. On 29 May, a large body of rebels called to 24-year-old Thomas Cloney’s home and “persuaded” him to join them. However some believe that Cloney was already a member of the United Irishmen and had been appointed Colonel at the outbreak of the rebellion. The rebel group under Cloney arrived in Enniscorthy to find it ablaze with corpses on the streets but they continued across the bridge over the Slaney to Vinegar Hill where thousands of rebels had assembled.

FORTH MOUNTAIN

The decision was made to march on Wexford. A rebel army of 10,000 men marched on the Three Rocks at Forth Mountain overlooking the town and set up camp.

Early the following morning, word came through that a contingent of the Meath Militia numbering about ninety was marching from Duncannon Fort to reinforce the garrison in Wexford. Cloney along with his friend John Kelly from Killanne and others assembled a party to ambush the King’s troops. The militia were all but wiped out in a fifteen-minute battle and the rebels took three cannons, arms and ammunition. (An obelisk commemorating the victory was erected on Forth Mountain on the 140th anniversary in 1938).

WEXFORD

The rebels moved on to Windmill Hill where they were joined by 2,000 men from Forth and Bargy. By now the rebel army totalled 20,000 men and the 1,200 government troops stationed in Wexford town retreated. For the short three weeks of this ‘Wexford Republic’ the rebels had control of the town and most of the county. During the occupation of Wexford, Cloney was known to have intervened on a number of occasions to help loyalists who were in danger of being killed by some of the less disciplined rebels.

The rebel leaders in Wexford planned to divide their forces into three columns and spread the rebellion towards Kilkenny through New Ross, into Carlow through Bunclody and towards Arklow and on to Wicklow and Dublin.

NEW ROSS

Under Beauchamp Bagenal Harvey, Cloney and his comrades were to move west for an attack on New Ross. The rebel force of about 10,000, mainly armed with pikes, assembled on Carrickbyrne Hill and moved on to Corbet Hill a mile outside the town. At dawn on 5 June, Matthew Furlong from Raheen, a friend of Cloney, was given a summons by Harvey to be dispatched to General Johnson who was in charge of the town’s garrison of 2,000 offering them an opportunity to surrender. Furlong, riding under a flag of truce towards the town, was shot dead. And so began the battle of New Ross, the bloodiest of the 1798 rebellion. The British had prepared defences both outside and inside the town. An advance guard of 500 insurgents led by John Kelly were instructed by Harvey to seize the Three Bullet Gate. After a fierce battle the rebels poured through the gate and fought their way through the streets and laneways of the town. After initial success, most of the British garrison fled across the bridge. But with some streets now piled high with dead and a great part of the town in flames, the rebels were eventually beaten back. When New Ross was secured, a massacre of prisoners, trapped rebels and civilians began and continued for days. Some hundreds were burned alive when rebel casualty stations were torched by victorious troops and more rebels are believed to have been killed in the aftermath of the battle than during the actual fighting. A total of about 2,000 rebels lost their lives. Reports of such atrocities brought by escaping rebels are believed to have influenced the retaliatory brutal massacre of between 100 and 200 loyalists on a farmstead in Scullabogue at the foot of Carrigbyrne Hill. The victims included men, women and children who were shot, piked and burned in a large barn.

Following their defeat in New Ross, the rebels rested back on Carrigbyrne. They later moved camp to Slieve Coillte where Bagenal Harvey resigned his command and was replaced by Father Philip Roche. Cloney was given the title ‘General’. When three English gunboats were spotted sailing down the River Barrow from New Ross, a detachment under the command of Thomas Cloney attacked them. Two of the boats made their escape but the third the ‘Louisa’ was captured. From here the rebel force, now under Roche, moved to Lacken Hill, about a mile east of New Ross. Cloney was dispatched by Roche to attack Borris House, Co. Carlow, the home of Walter Kavanagh. It was known that a large supply of military equipment was stored in the house. Thomas reluctantly carried out the attack; the Kavanaghs were good landlords to his own family. The house was badly damaged in the attack but it was too heavily defended by the military and the attack was finally called off.

FOULKESMILLS

From Lacken Hill, Cloney and the rebel army moved on towards Foulkesmills, about twelve miles away on 20 June. Word had reached them that a British force under General John Moore had reached the village. With reinforcements joining them from Enniscorthy, the two sides met at Goff’s Bridge just east of Foulkesmills. The British were armed with rifles and cannon while the insurgents numbering about 600 fought with small arms and pikes. After heavy fighting for four hours, the rebels learned that Moore’s forces were on the point of being reinforced and so, running low on ammunition, they retreated to Wexford town.

END OF REBELLION

Goff’s Bridge proved to be Thomas Cloney’s last battle of the rebellion. They received the grim news of the defeat at Vinegar Hill on 21 June. 20,000 British troops had arrived in Wexford and surrounded the rebels at Vinegar Hill before shelling them and attacking with cavalry. The rebels were now fleeing towards Wexford and the defeat had effectively put an end to the rebellion. Cloney was pressed to carry a message of surrender from Wexford to the ruthless Commander-in-Chief, General Lake at Enniscorthy. He rode with red-coated Captain O’Hea through fleeing rebels and the pursuing military towards Enniscorthy, passing “soldiers still engaged in the work of slaughter…in one place we beheld men with arms, and some with legs off, and others cruelly mutilated in various ways…” Cloney wrote later in his ‘Narrative’.

The following day he returned to Wexford with the advancing militia. But his horse had been confiscated and he was forced to make the journey on foot. As the army reached the town, Cloney slipped away. The hunt was on for rebel leaders who were summarily tried and hanged on Wexford Bridge. Passing through the Bullring, Cloney was spotted by a loyalist who sought his arrest. A loyalist friend Anthony Rudd resisted the arrest and spirited him away to a cousin’s lodgings where he stayed for four days evading capture. On the fifth day, dressed in a yeoman’s uniform, he slipped out of town to Ferrycarrig and eventually on to his home in Moneyhore. His dying father and three younger sisters had believed he was dead.

While hold up in the house Thomas accidentally shot himself in the thigh with a pistol. He had to get medical attention and eventually travelled in disguise to a friend’s house in Enniscorthy. He was bleeding so much that he had to see a doctor. After a few days his whereabouts were discovered and he was removed and placed under guard. Representations were made on Cloney’s behalf and after taking an oath of allegiance, he was granted ‘protection as a rebel officer’.

ARREST AND IMPRISONMENT

His father died the following month and it was March 1799 before Thomas had recovered enough to return to Moneyhore. He had many enemies within the loyalist community who believed he should have hanged for his part in the rebellion. In May 1799 he was arrested at Borris House and charged with leadership of the United Irishmen and falsely of a murder at Vinegar Hill. He was courtmartialed spent nearly two years in Wexford Jail until his release in 1801 and ordered to leave the country for two years. Thomas was now aged 27. He left Ireland for Liverpool, returning to Dublin in May 1803. According to the memoirs of Miles Byrne, Cloney was involved in the planning of Robert Emmet’s failed rebellion three months later. In September he was arrested and taken to Dublin Castle where he was interrogated about his part in Emmet’s rebellion. He denied any involvement but spent the winter in solitary confinement in the tower of the Castle. In February 1804 he was transferred to Kilmainham Jail with his physical and mental health now deteriorating. It was November when he was finally released on health grounds.

He lost the lease on the farm in Moneyhore and so settled with his sisters in Graiguenamanagh, Co. Kilkenny where the family still had rented lands nearby in Co. Carlow and where he was to spend the rest of his years. Cloney continued to get involved in national politics and in 1807 was present at the fatal duel between his friend John Colclough of Tintern and Willam Alcock of Wilton Castle. Colclough was killed in the duel near Ferrycarrig. He continued to involve himself in political affairs in Wexford, Carlow and Kilkenny. He also became an enthusiastic supporter of Daniel O’Connell and his efforts to secure Catholic emancipation through constitutional politics. In 1832, now aged 58 and still a bachelor, Cloney published his ‘Personal Narrative of 1798’. He became a committed resident of Graiguenamanagh and participated in the social and religious life of the community. He had come to be looked on as an elder statesman and had visits from leading politicians of the day including O’Connell. Thomas died at the age of 76 in 1850 and was buried in the company of his mother’s ancestors in nearby St. Mullins.

© Des Kiely / With grateful thanks to Eileen Cloney of Dungulph Castle for her assistance and John Joyce’s 1988 book ‘General Thomas Cloney’.

Thomas Cloney wrote his own memoirs of 1798 and his involvement. An extract from this: “I at this time was about twenty-three years of age and lived with my father, Denis Cloney, at Moneyhore, within three miles of Enniscorthy, and in a direct line from that town to Ross; he rented large tracts of land, both in the Counties of Wexford and Carlow, a good part of which his father left him in possession of, and the remainder he acquired by industry, and altogether they would, if let, produce him an interest of several hundred pounds a year. . . . I was an only son, and had three sisters, all younger than myself and unprovided for: and as my father was aged, and his health then in a very precarious state, they might be considered almost without any other protector but myself, and they were truly dear to me. . . . I was a Catholic, and that placed me in those days on the proscribed list, and under the ban of a furious Orange ascendancy, and their rapacious satellites, a blood thirsty Yeomanry, and a hireling magistracy, who looked forward to the possession of the property, not only of Catholics, but of liberal Protestants, either by plunder or confiscation; where then was the alternative for me? It became indispensable to divert their attention from those objects by meeting them in the field. . . .”

Read the full memoir here (Google Books: Thomas Cloney – A Personal Narrative of Those Transactions in the County Wexford, in which the Author was Engaged, During the Awful Period of 1798)

A fascinating history of the Kavanagh’s of Mangan.

I am a descendant of a Kavanagh born at Mangan to a Thomas & Catherine.

Their son is my grandfather Edward and all of the above are buried in the Corrig graveyard in the grounds of St John’s Manor Enniscorthy .

Grandfather purchased St John’s when he was in his early 30s. The property at that time was a substantial house and some 300 acres.

We can trace Edward to Mangan and being the son of Thomas but beyond that we have no clear history of.

Could these be the descendants of Denis?

Hi John, good to hear from you. I wonder if your grandfather Edward’s parents might be Thomas Kavanagh (1831-1891) and Catherine Bracken? I also see a Thomas Kavanagh (1872-1951) in our tree, but no name for his spouse. If you want to send me a few more details I will be happy to take a look through my notes.