Strange Sequel to Wreck of an East Indiaman at Cape Agulhas — Mutineers Who Wore Gowns of Silk and Chinese Satin

Copy of an article by Dr. E. E. Mossop, published in the Cape Times, 8th July 1930 [Source: >].

BY DR. E. E. MOSSOP. . . Amongst the thousand—no—million and one lesser manuscripts in the Cape Archives are many which are unlikely to be published, for the very reason that they are lesser manuscripts, during the present generation. Yet it is a mistake to minimise their importance, for from the most unpromising there may fall, in some casual sentence, a flood of light upon forgotten incidents or customs or place names, which repay its study. Whether it be an official document written in the intriguingly pedantic but poetic High Dutch of two or more centuries ago or some human and less stilted document from the pen of a forgotten burgher, it will be found to have an interest for the student of the past. To the student of Old Cape place names, they constitute a field for research which he can ill afford to ignore.

Of such a nature are two documents preserved amongst the “ Attestation ” which tell of a shipwreck in Struis Bay at Cape Agulhas in the year 1722 and of a journey via Onrust to the scene of the disaster. On November 18 of that year, the D.E.L Company’s ship, Schoonenberg, approaching the Cape from the East Indies in calm weather, was piled upon the rocks near a cove still called Schoonenberg Bay, near the site of the present Agulhas Lighthouse. Some ten days later eighty of the crew, with the first and second mates, appeared at the farm of the Heemraad Philip Morkel below the kloof of Hottentots Holland.

Total Wreck

They stated that Skipper van Soest, with some twenty men and a couple of slaves, had remained ashore near the wreck. They themselves had left because no water was to be obtained there, only half a cask being left. They were unanimous in their declaration that nothing could be done to save either the ship or its cargo. The truth was that a mutiny had broken out immediately the ship struck and the men, after plundering the ship, had landed on floats, despite the captain’s protests. The latter had remained aboard the ship. He had landed (they said) very drunk and had narrowly escaped death (this they did not say) at the hands of the mutineers. The Governor de Chavonnes at once sent commissioners to conduct an investigation at Stellenbosch, and it was by the order of these commissioners that Cornelis Valk, described as Skipper and Equipage Master (Equipagie Mr), and J. Pleunes, Secretary to the Heemraad of Stellenbosch, were sent with two wagons, some slaves and provisions to rescue the captain and, if possible, salvage the ship’s papers.

The short story of their journey is told in a signed paper headed “Diary kept on the expedition to the wrecked Company’s Ship Schoonenberg.” They left on December 2, and that night were below “the steep heights of Hottentots Holland Kloof, camping at 10 o’clock at the Palmiet River. Next day they passed “de Knofflooks crael” and “the so called houw Hoek.” Beyond Houw Hoek Station the road they followed may still be traced across the mountain range to the Bot River valley, for it did not at that time follow the deep ravine which today accommodates both rail and road. At the foot of the Old Houw Hoek Pass in the Bot River Valley beyond, they sent one of the wagons “to the left hand to the warine badt ” (i.e., to Caledon Hot Springs) while they turned towards the sea “ aan de boter rivier,” until having passed the abandoned castle post of one Wessel Pretorius, they arrived at 4 p.m. at the sea-shore at the “ Groote Valley ” or Great Vlei “ which place, so our men said, was called Onrust, because of the everlasting droning ” (continueele gedreenz) “ of the sea.”

Danger Point

They saw to the south-east a far-extending point of land which “ in the opinion of the Equipage Master must be Cape Agulhas of the Chart.” It is of course Danger Point they saw, for Agulhas was as yet quite out of their view. On December 4 they'” followed the mountain foot and passed over “ de Onrusts rivier ” where the wagon driver- found a stnall halberd or pike, and by noon they grazed their oxen at “de mossel rivier.” Their route thus far will be familiar to any who have visited Hermanus, that which followed will be well-known to all who have followed the coast line beyond. They came to the “ Kleyne Riviers Valley, rich in fish and fowl,” now the lake beyond the Riveira Hotel (die tai ryk van visschen en vogels was, hier reeden wy ’t hooge gebergte after uyt, langs de duynen by ’t Strand), and having left the mountains behind them, followed the long white beach which ends at the. caves near Gans Baai. A low mountain ridge acts,as a backbone to the long Danger Point peninsula and sheltered by its farther slopes is still a farm called Uyle (Owl) Kraal on Uyle Kraal River, so we may follow them when by sunset they were at “de Uyle Craels rivier by ’t groote renoster bosch op de plaats van den Landbouwer Hendriecq Klopper.”

Thirteen sailors who »were later proved to have been the leading mutineers were found here, they defiantly refused to return to the wreck. Next day with “Aurora gleaming in the crystal clear expanse of Heaven,” our poetical travellers set out with Kloppers’ fresh oxen and a free black as guide. At Vyle Kraal the “wagen padt”—which could have been no more than a sand track—ended, and they made their way by means of the elephant paths through a bush of which now only Baard Scheerders Bosch (Beard Shavers Bush) remains, they saw an island (Dyers), and at noon were at “de buff els jagt,” a rocky spot along the coast still so named and well known to enthusiastic rock fishermen.

At Onrust

At sunset they camped below “de Zoetendaals Valley gebergte,” not be it noted the Bredasdorp range, but the chain of limestone hills which runs east from Zoetendals Vlei, now called Anysberg. The salt pans which lie east of the vlei were passed next morning, and here an elephant was seen, but it disappeared without affording them a shot. The wreck was sighted at a distance of two hours after passing Zoetendals Vlei.

Captain Soest (who welcomed them with tears) was found together with his slave and the ship’s purser. After their return to the Cape the purser, who signs himself Paulus Augier Jnr. wrote a “Relaas” or relation of the wreck of the ship Schoonenberg, at the request of the Governor and Council. He tells Their Honours of his fright when the ship struck, of the noise and shrieks and curses which followed. When he came upon the half-deck “the tears were in the eyes and the hands in the hair.” He tells of the flight of the crew with their plunder, and of the Captain’s heroism (and his own) in remaining on the doomed ship.

If we are to believe him, he saved this officer from being cut down by a sailor armed with a cutlass. He admits, however, that when they landed three days later the Captain was drunk, and that he, Paulus, “gave my pistols to their keeping in order to quiet them and stole softly hence with abuse and a few dondere-blixems to keep me Company.” The mutineers called into question the captain’s seamanship, appealing to the mates to confirm their accusations. “Tis unbelievable, your Honours, what a noise and disturbance there was amongst the men. They began at last to abuse and push even me about and I took a blow here and there which I still feel after fourteen days, and had not the Boatswain, who luckily passed by, come to succour me it would have gone hard with me.”

Unhappy days for Paulus followed. He sought protection from the mates (who appear to have been neutral) when “the blows fell thick as rain.” He had secret interviews with the captain, who “ spat blood and seemed sore mishandled.” One day the first mate took leave of them “with a small halberd and a bottle of water on his shoulder on pretext there was not sufficient here. The captain wished the mate well and gave him a letter for Their Honours. Then matters grew worse, for the remaining mutineers threatened to hang the purser because he had rescued the ship’s papers from the wreck.

Sore Mishandled

But even mutineers have ‘peaceful moments. “Once,” he says, “when I went to fetch me a little pudding there came the foremost of the ‘ belhamels * (i.e., belwethers or ringleaders) in gown of silk with Chinese Satin of Tung-Keang for his Sash (in een syde Japon met een tunkings pillang voor syn cherp). He leaned upon my shoulder as though my greatest friend. He asked me what I thought of life and when I felt disposed to take my leave. I said that we were resolved to await help from the Cape, he replied that I would wait long and said he, ‘We are resolved to prepare the ship’s boat and clear out,’ and he warned me that he’d surprise and bind the skipper, who had disappeared, at night whilst he was drunk.”

It cramps the style of Paulus, with his flood of indignation and words imported from the East to put him into English, but it took eleven pages of the Company’s good parchment to tell Their Honours of his sorrows. They leave one wondering what the Governor and Council thought of him, and if the mate’s half-halberd was the one picked up in Onrust River. It is pleasing to know that he safely reached the Cape and was commended, and that the “ belhamels ” got their deserts. On the return journey, when they were camping by night at Mossel River, where Mr. E. Poole now lives*(“agter een groot bosch aan de mossel rivier”), they had a beast of prey, perhaps a leopard (“ongediert”) amongst their oxen, and found five wounded in the morning.

Schoonenberg Bay at Barry’s Store near the Agulhas Lighthouse looks peaceful and picturesque in the sunlight of a summer day, but for those who have read the “Relaas” of Paulus, this bay will always bring to mind the picture of a mutineer ringleader in a plundered gown of silk, who leans in friendly familiarity upon the shoulder of a frightened ship’s purser.

This article was written in July 1930, one of the earliest published versions of part of the Schoonenberg story. It is based on the notes of Paulus Augier, who was the ships accountant and Captain van Soest’s right hand man. The bias against the sailors (“mutineers”) is strong. It is worth noting that no “just deserts” were given to the alleged mutineers by the authorities in the Cape, rather it was van Soest that was found guilty of negligence and stripped of rank and pay – while none of the sailors were indicted or penalised, and eventually returned to Holland with full pay. From the perspective of the VOC, it was the Captain that was the guilty party.

Beach dress, rebel style

“He asked me what I thought of life, and when I felt disposed to take my leave“

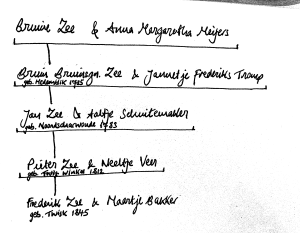

The description of the rebel wearing a Japanese silk rope is striking, with a scarf made of shiny metallic pieces from “Tunking”. Tunking is an old Dutch description for today’s Burma, or Myanmar. Augier doesn’t mention who the rebel is, but there were only a few ringleaders – and Bruno Zee was one of them, according to van Soest.

R>> The original “Relaas” from Augier – find it and read again.