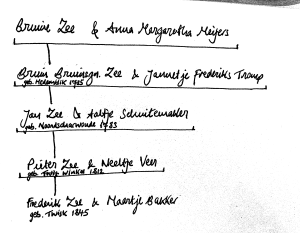

Bruin Bruinszoon Zee was the first Dutch-born Zee, born in Medemblik in 1735 to Bruno Zee and Anna Margaretha Meyers.

In his twenties, he was a sailor and ships carpenter, working for Capt. Jacob Hendriks Jonkman on board a ship named the Margaretha en Gijsbert Galleij. Homeward-bound on one voyage in the summer of 1759, he and his crew mates found themselves the subjects of a terrifying pirate attack off the coast of England.

This is the story of that voyage.

Writers note: In telling this story, I’m realizing just how much has come to light about this ancestor of ours. For all of us Zee’s, Bruijn Bruijnzoon Zee is a direct ancestor – for me, he is my great-great-great-great-grandfather. When I first started putting together the family tree in 1993, we knew almost nothing about him – born in 1735 in Medemblik, married in 1760 in Lutjebroek, died in 1798 in Noordscharwoude. That was it. Nothing even indicated his profession. And now – in 2024 – this pirate story is just another piece in the progress of a fascinating life. His father Bruno Zee’s life story is one that will likely remain unrivalled, and yet Bruijn is beginning to do just that. This pirate encounter in 1759 would have been quite terrifying – yet he lived to tell the tale a few months later. And it’s thanks to Bruijn’s own telling of the story a few months afterwards, amongst a group of his shipmates, that we are able to find it again today. It turned up in a collection of notarial documents which for centuries had been hard to access. Here’s my retelling of the story some 265 years later!

Floor stones, fruit, wine and olive oil – cargo for the Netherlands

On May 3rd, 1759, Bruin Zee and the crew of the Margaretha en Gijsbert Galleij started taking on their first cargo in the Italian port town of Livorno, just south of Pisa. The majority was stone flooring, which would end up being used in newly built houses in Amsterdam. Additionally, the crew took on Italian wines and general cargo.

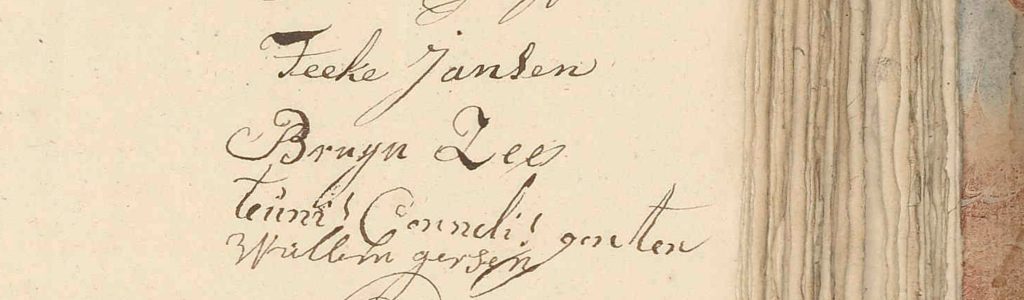

Bruin was noted as the ship’s carpenter. The other crewmembers were: Dirk Tjalles, Helmsman, Teeke Janssen, Boatswain, Tennis Cornelisse Gortter, Cook and Willem Gerritsz, Sailor.

Loading took a little over 6 weeks, with the voyage getting underway on June 16th. The first port of call was Genoa, which they reached on June 20th in order to undergo quarantine. Here they received a guard on board the ship. Due to rough conditions in the harbour, they could not leave until the 26th of June, when they set sail for Porto Maurizio, close to the French border and not far from Nice, to collect an additional shipment of olive oil for the Netherlands. From there, they continued chugging along the Côte d’Azur, stopping at St. Remo, and finally Menton, stuffing in as much local fruit as they could into the storage spaces on board.

The ship was now readied for the trek back to Holland – tarpaulins over the hatches, masts fully rigged, all cargo secure. The date was July 4th, 1759.

A storm at the Strait

Progress across the western Mediterranean was slow. It took four full weeks to reach the Strait of Gibraltar. Nearing Malaga, on August 3rd, the fine weather they had experienced to date was replaced by a growing easterly wind. Six miles offshore, and with visibility worsening, the wind grew to storm force. They took in the foresails and topsails, and reefed the main.

The storm continued through the night. The ship took the full force of the storm. It pitched and rolled, and large floods of water went over the decks. By morning, the intensity had eased, but strong winds and high seas made progress slow. It took another full day to reach the narrow passage through the Strait, passing Gibraltar on the starboard side.

Into the Atlantic

Bruin Zee and his crewmates were now out into the Atlantic Ocean, and joined the route back to Holland that was also taken by his father Bruno Zee, back in 1724, when he had returned home onboard the VOC ship Clarabeek. They passed Portugal, sailed across the Bay of Biscay, and entered the English channel on September 17th with mostly easterly winds. The Atlantic portion of the journey had been relatively favorable with no major storms, but still progress had been slow going – a month and a half from Gibraltar to abeam Brest.

Pirate Attack

A week or so later, they reached Beachy Head. It was here that they went close to shore to pick up a Texel pilot, who would help them navigate into the harbour on reaching home. The following day, September 26th, sailing into a north-north-east wind, an unknown vessel was sighted coming in their direction.

Having already collected their pilot, Bruin and his crew were not expecting any more contact from shore, and so the sight of the unidentified ship growing larger as it came their way was of strong concern. Who could it be? They were now less than a mile offshore, so it could be a friendly fishing vessel or perhaps another Dutch ship.

The sight of eight armed men in the boat made clear the situation that was developing. This was not a friendly vessel: these were pirates. Pirates armed with axes and cutlasses.

The cutlass was a favorite weapon of pirates – a short, slashing sword. Historians have recorded their use by pirates as far back as 1667. The pirate knew full well how to take advantage of every part of this sword effectively as a weapon during a boarding. The crew unsheathing their swords as an intimidation was often enough to capture a surrendering vessel. Strikes with the basket or flat of the blade were common uses as well if any of the captured crew were to get out of line.

Bruin and his crew had little to defend themselves with, and it made more sense to comply with the demands of the hijackers. Once aboard the Galleij, they demanded to know of the valuables aboard. Of most interest to them was a set of chests, ten in total, containing fine Italian linen. They helped themselves to these and offloaded them into the pirate boat, along with other valuables.

After an hour and a half, the ordeal was over. Thankful that their lives had been spared, the crew gathered themeselves and set sail for the last part of their voyage home to Holland

Arrival at Marken, and Amsterdam

On October 11th, Bruin Zee and his crewmates arrived at the island of Marken, just outside Amsterdam. They had already offloaded some cargo at Texel, in order to be light enough (and therefore out of the water) to sail through the shallow waters of the Zuider Zee.

A storm that same day put paid to the offloading process, and so they had to wait three more days before they could complete the offload on October 15th. On October 18th, 1759, they sailed as far as the lighthouse at Amsterdam, anchoring due to further poor weather. Finally on the following day they were able to tie up in Amsterdam itself, at the “Nieuwe brug boom”.

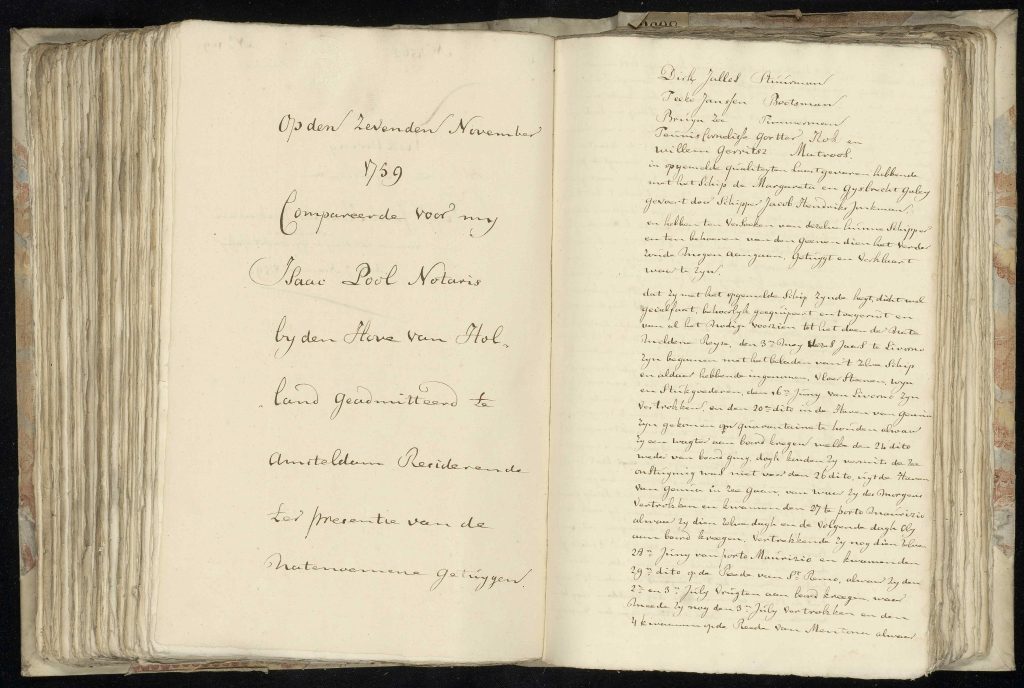

Recounting the story to Isaac Pool

It was customary in these times to document any irregular voyages by way of notarial deed. This would alleviate any suspicions from the merchants involved that the crew might have pilfered the goods themselves. On November 7th, Bruin and his fellow crew members paid a visit to the notary Isaac Pool. At this time, his offices were on the Kalverstraat.

We can see Bruijn Zee’s signature on the sworn testimony of the voyage >

Documents

The original story as told to Notary Isaac Pool in Amsterdam, in November 1759 >